One of the first things you hear, as a writer, is ‘write what you know’. This is at best ambiguous advice, as the great joy of writing comes from exercising the imagination, from learning and writing about things you don’t know. And wouldn’t it be tedious, frankly, to only write about your actual experiences? I’d never be able to write a murder mystery, for instance, due to a lack of personal research that I have no intention of remedying.

However, I find real life experience very useful when it comes to creating scenes. The better I know a place in reality—the better I remember not only how it looks, but how it sounds (is there traffic noise? Or just the wind shushing through the dunes?), how it smells (brine? earth? smoke?), how it feels (the coarse rasp of sand, the smooth slick of oil)—the better I can bring it to life for my readers.

One such place for me is the Isle of Mull, in western Scotland. I’ve lived on the island for twenty years, and my first four novels are at least partly set here. In Walking on Wild Air I describe an unnamed island: its white-sand beaches, green fields and heather-clad hills, its views of distant mountains, and its small towns and single-track roads. All my descriptions, from the opening ferocity of a thunderstorm to the peaceful dance of hilltop grasses in a gentle breeze, come direct from my own experience.

The Calgary Chessman is the first in a trilogy of archaeological romances with a contemporary setting, and it opens with a walk along the sands of beautiful Calgary Bay in spring.

The wind was too cold. I was a fool to have come out without my coat: my calendar said it was spring, but no-one had told the wind off the sea. Sand stung my legs as I plodded down the beach, meandering just above the high tide line. Sparse grasses bound the sand around their roots, but much of the fine, white powder was loose, and the sea breeze blew it around my feet…

…I pushed my hands into my pockets and pulled my cardigan more tightly around myself, but the chill air crept in anyway.

Is it working? Do you feel the chill? Later we visit the bay again, busy with visitors on a summer’s day, and Cas Longmore, our heroine, walks around the headland to gaze out over the sea towards the other islands of the Inner and Outer Hebrides.

I climbed steadily for a few minutes and then, as I turned the headland, the hubbub died away and the still clearness of summer air enveloped me. A slight sea breeze sprang up and I tucked my hair behind my ears, although it blew straight out again. I stopped and gazed northwest across the vast, blue ocean, feeling the heat of the sun strike square between my shoulder blades, as palpable as a physical blow.

Calgary Bay is beautiful in any weather, be it a gale off the sea so strong it dents the eyeballs, or a bitter winter trudge in full wet-weather gear, hunching your head between your shoulders against the icy strike of a hailstorm, though it’s at its loveliest on a calm, warm day, when the white sand and turquoise sea are as inviting as any tropical resort. But watch out:

Sam charged into the sea and straight back out again, hardly more than damp above the knee. “It’s freezing,” he shouted. “I thought it was supposed to be summer.”

…”It’s always cold,” I reminded him. “You’ve been here before.”

His face was rueful. “I never remember,” he muttered. “It looks so shiny and blue, and the sun’s so hot, and I always think it’s going to be warm.”

I’ve seen the Bay in all its weathers and I hope I’ll pay many more visits to add to my memory stock. It’s a very different story when I describe the other touchstone location in The Calgary Chessman: hidden Huna Bay in northern South Island, New Zealand. ‘Huna’ is a Maori word meaning ‘secret’, and the hidden secret of the book is that the location is as hidden from me as it is from you. I grew up in New Zealand, and had two notable missed opportunities to visit the glories of Abel Tasman National Park, both trips cancelled at the last minute after a great deal of forward planning. To my disappointment, I’ve never made it back. But Cas Longmore’s grandparents run their family farm on the edge of the National Park, and Huna Bay is the sanctuary Cas’s mind goes back to in times of danger or loneliness.

Here I’m using the full power of my imagination, buoyed up by the descriptions of friends or other writers, and many photos and paintings that I’ve seen over the years. This is the polar opposite of ‘write what you know’. One day I hope to go there, and to walk the Abel Tasman track or kayak the shoreline, to see how accurate I’ve been. Here Cas is dreaming of her favourite place in the world.

At first blinded by the sun striking molten silver off the sea, I could see nothing but the shocking turquoise of the water. Ahead, the warm sand edged away into a sparkling sea. The sun stood high in the vault of the sky and bathed me in its beneficent glow.

I turned a full circle, taking in the crescent of beach backed by a small cliff, itself topped with a green tapestry of leaf, fern, and creeper; a verdant brocade spilling over the cliff and weaving itself over every surface. At the foot of the cliff a tiny creek emerged from a green pool, filled by the constant curtain of drops trickling down the cliff face.

If you’re thinking about taking up the pen (or keyboard) of the serious writer, or if you already write and are looking for ways to extend and improve your work (and we are all, always, doing that) it can be both pleasurable and useful to sit down, close your eyes, and imagine a single location in detail. Get all those senses working: really feel yourself to be there. Then, while it’s still fresh in your mind, write it down. It may never end up in a book, but I guarantee it’ll sharpen your sense of the place you’re trying to describe.

I wrote my first description of Huna Bay as part of a mental health exercise, where I developed an imaginary safe place to which I could retreat in my mind if real life became too difficult or threatening. It remains my sanctuary, just as it is for Cas, and I hope its magic never fades.

The Calgary Chessman is available in e-book and paperback, and if you decide to read it I’d be delighted to hear what you think of it. I hope its locations are evocative, and that one day, when all the present troubles and restrictions are over, you have the opportunity to visit it in person, and not just via my imagination.

mybook.to/TheCalgaryChessman

You’re all invited to my Facebook event 8am-midnight BST on Sunday 26 July 2020. Drop in any time to join the conversation, with music, competitions, and book-related chat.

You can follow me at my Facebook page and friendly group, on Twitter, or my blog, The Knitted Curiosity Cabinet, and I’m always happy to answer questions on Goodreads.

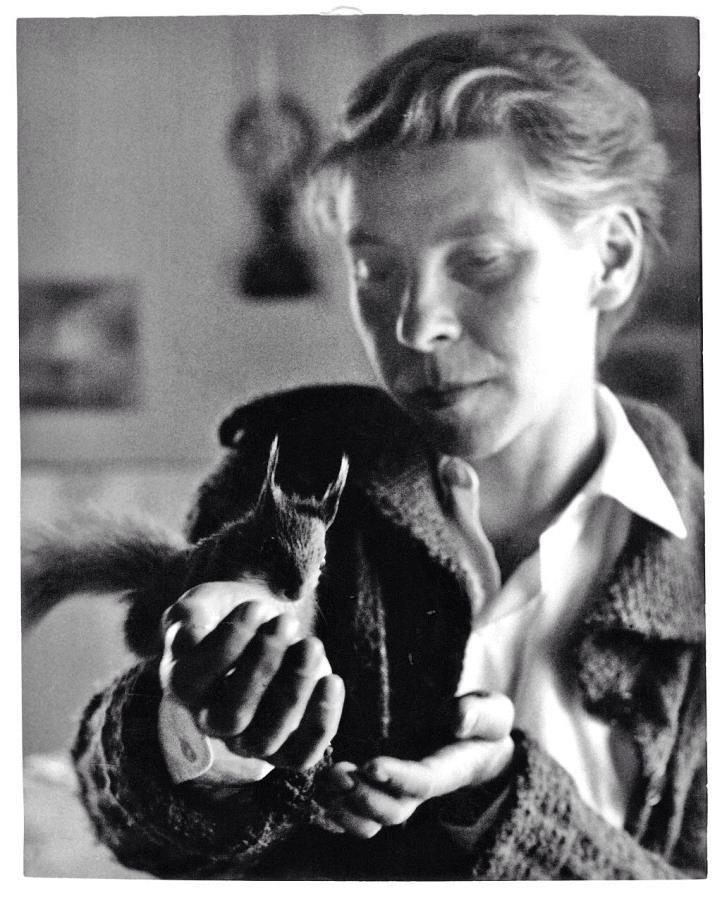

Author pic by Sam Jones at Calgary Bay, Isle of Mull

Recent Comments