I read my first Le Guin in late childhood, when I was in my first flush of Sci Fi discovery, moving on from fairy tales and fantasy to stuff that had more meat to it. She has been my favourite living author ever since. Until today.

She stands head and shoulders above all others in my personal pantheon, so what is it that I value so much about her? What is so special?

For a start, as a female writer, I owe her an immense debt. Growing up I didn’t consciously gravitate to male writers. I read whatever I could find that looked good to read, and in the arena of science and Sci Fi the writers were virtually all men. But at age 14 or so, back in the mid 70s, I was astonished to discover that some of my favourite writers were in fact female. Women who’d had to disguise their sex under initials or gender-neutral names in order to get published at all. And as for the hubris of daring to write science-based fiction? Andre Norton, C.L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, L Taylor Hansen, and most of all U K Le Guin: I salute you. You changed the world. According to Wikipedia, six women have been named Grand Master of science fiction by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Andre Norton was named in 1984, and Le Guin, at last, in 2003.

I do know that the sex-bias of early Sci Fi publishing is disputed, and there were plenty of writers who didn’t hide their sex under gender-neutral names, but it was and remains my perception that it was much more difficult for women writers to be taken seriously, particularly if they were writing ‘hard’ Sci Fi.

She’s been a vociferous and challenging voice up until very recent times, outspoken in her advocacy of books and writers and the universe of words. In 2014 she made a passionate speech about the value of writers to society, at the National Book Awards in New York after accepting the 2014 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters .

“Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom – poets, visionaries – realists of a larger reality.”

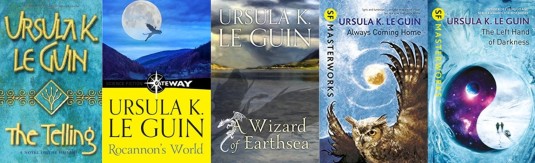

One of my favourite Le Guin novels is Rocannon’s World. It begins with a myth, Semley’s Necklace, which tells the story of the lost treasure of the Angyar, and the young woman who enters a dark cave to retrieve it, only to return home a few days later to be greeted by her baby daughter, now a grown woman. It cleverly takes a well known fairytale trophe, and explains it in terms of relativity. In fact, when I later came to study Einstein’s thought experiments and the Theory of Relativity, Semley’s Necklace was the strand on which I strung the precious (and elusive) beads of my understanding.

In Rocannon’s World the hard science of space travel, and of relativistic effects on aging and communication, rub shoulders with a generous and perceptive assessment of humanity and a convincing portrayal of alienness. Le Guin’s own invention of the ansible (enabling instant communication between star systems, although physical travel could take a generation) has spread throughout all the universes of Sci Fi, and we hardly remember a time when it wasn’t taken for granted.

She made magic wonderful again. I have my favourites (I’ll always be a Tolkienophile) but their worlds are distant from ours. We are shut out. Even those worlds (such as Narnia) which connect with ours are open only to a few. But in Earthsea, and the arch-mage Ged who began his life as a goatherd on the isolated island of Gont, we find a world that is open to all of us. The reason Earthsea’s inhabitants seem so accessible, so human, is that its mores and philosophies are taken from the Tao. I didn’t come to study the Tao until quite late in my life, but when I did it felt like coming home to an old friend, its cadences were so familiar.

Le Guin creates a philosophy of story-telling in one of my personal favourites, The Telling which was first published in 2001. Here the human perspective, the Haining Universe in which so many of her books are set, comes up against a peculiar military dictatorship, the prime focus of which seems to be to bar literacy, to destroy books, and to wipe out learning. In travelling this world, human envoy Sutty gradually begins to understand what motivates the people of Aka, and opens a doorway into her own soul. At heart, all Le Guin’s stories are about the individual’s search for meaning, for stories that help us to make sense of our lives, and The Telling shows that in a particularly wonderful way.

In Always Coming Home, Le Guin changed the rules again. Part memoir, part half-lost history – she calls it an archaeology of the future: an imagined California in which everything has changed, but people find ways of living that are meaningful and rewarding no matter how hard the environment. Gentle, elegiac, deceptively simple – a series of moments like beads on a string; you can read the book from cover to cover, or dip into it, or pick only the poems or only the narrative, as you please.

But here too we recognise the scholarship, the scientific basis for her work. See all that stuff in the news at the moment about the effects of plastic microbeads on the oceans? Le Guin predicted it in 1985.

Perhaps her most famous work, The Left Hand of Darkness, is a more difficult beast. I didn’t enjoy it as a teenager. I needed to live life a bit before I was ready for its politics, its difference. I sometimes feel now that Le Guin overdid the gender-bending aspects of her stories, and the peculiarities of Winter and its non-gendered natives is a particularly strong example. But creating a world in which everyone is of the same sex (or no sex, most of the time) and then dropping a lost and as usual confused earthman into the middle of them, enables her to play mindgames with us and she challenges our expectations. I expect I’ll still be reading this book into old age, and it will always have something new to tell me.

RIP Ursula Le Guin. Rest, of course – you’ve earned it. But don’t expect us to stop arguing about your stories. Long may that continue.

Recent Comments